On May 25, 1927, car manufacturer Henry Ford announced that he would stop building the Model T, more commonly known as the Tin Lizzie.

He had built 15 million of them. On the same day, Mr. and Mrs. George Sampson announced the birth of their son Fred; that’s me.

As a result I will, on May 25th of 2017, have the privilege of celebrating my 90th birthday. If doctors knew then what they know now, I’m sure they would have said, “He has foodservice in his DNA.”

The year 1939 marked the beginning of what was to become World War II. The United States would not enter until December 7, 1941, so prices in the USA were still relatively stable.

A loaf of bread cost 8 cents; a gallon of gas, 10 cents; hamburger meat, 14 cents a pound; a pound of cabbage, 3 cents; and Wisconsin cheese, 23 cents a pound.

The median family income was $1,500 a year.

I can remember brewing coffee in 5-gallon urns and serving it in green band cups for 5 cents per, with little glass creamers (real cream) with lids, all of which had to be washed and filled by hand after each usage—talk about labor costs! Bagels were still a predominantly Jewish bakery product and not competing with doughnuts.

Speaking of doughnuts, the Mayflower Coffee Shops were making doughnuts on small machines in their front windows, which in turn created large crowds out front. Their motto was: “As you ramble through life, brother, whatever be your goal, keep thy eye on the doughnut and not the hole.” Who could possibly ever forget prose of that literary quality!

Cafeterias were still very much in vogue, as were the equivalents of today’s QSRs: Bickford’s, Chock Full o’ Nuts, White Tower Hamburgers, and White Castle (still growing strong).

Horn & Hardart was operating cafeterias in New York City and Philadelphia and their automats were not only the original food vending machines, but they also became a tourist attraction for out-of-town visitors.

F. W. Woolworth Company and its 5- and 10-cent stores were the largest foodservice company in America, having lunch counters in all of their 1,200 stores.

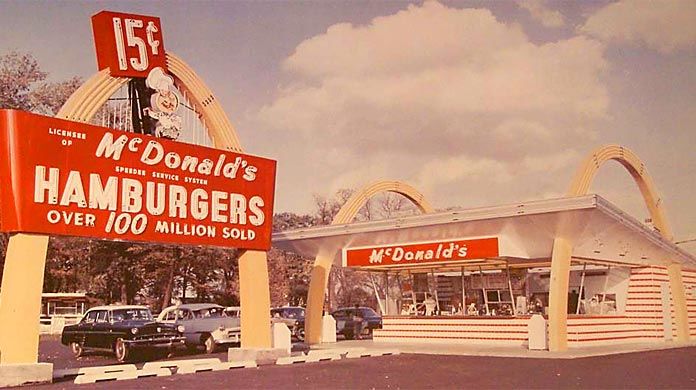

The Childs Restaurants company operated what might be called, by today’s standards, upper-middle-class tablecloth restaurants, in about 25 cities throughout the Northeast. Sardi’s and the 21 Club were at the top of the game. “McDonald’s” was a farm operated by an old man and “subway” was something you rode and not ate.

The war brought with it rationing of gas, which affected the highway eateries, and the rationing of all foods changed America’s eating habits. Unfortunately, it also gave birth to the black market, leading to inflation.

This occurred despite the fact that the government formed the Office of Price Administration, whereby all pricing and increases had to be approved. Some folks maintained that rationing was just a ploy by the government to make the population more sensitive to the war.

Don’t believe it. I was there. Young men and women were not only putting their lives on the line, but to this day thousands of Americans are buried all over the world as testimony to our involvement.

The end of the war found the country anxious about its future and there was general agreement we would never be the same. One of the unforeseen events was how many service men and women would take advantage of the GI Bill of Rights, one of the greatest Acts that Congress ever passed.

By 1947, applications for both college and home loans were changing both the housing and education businesses. The explosion of suburbs was about to take place, and new communities meant new foodservice establishments and opportunities.

Having weathered the impact of war, Howard Johnson, the “Host of the Highways,” was ready to expand. Not only was he opening new company stores, but his franchising program met with great success and orange roofs were appearing everywhere including in the new postwar phenomenon of suburbia.

Howard Johnson became a pioneer in the toll-road feeding segment when he was awarded with the mother of all toll roads, the Pennsylvania Turnpike. In a few short years, Howard Johnson’s orange-roofed units were serving their frankforts (that’s not a typo; that’s what they were called), Ipswich clams, and 28 flavors of ice cream in about one third of 48 states (Alaska and Hawaii were still waiting in the wings for statehood).

In addition to the housing boom taking place across the country, Congress was about to pass another life-altering bill, the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act, which approved the building of 40,000 miles of interconnecting roads to cover the entire United States.

The Act’s major purpose was to allow for the deployment of troops and war materials in the event of a national emergency. The roads were fashioned after Germany’s autobahns. One of the by-products was to create hundreds of interchange villages consisting of food service, lodging, and service station facilities.

In many instances these interchange villages eventually attracted office buildings, truck terminals, outlet centers, and new housing. This was the beginning of transforming the face of rural America.

Another aspect of foodservice growing at a prodigious rate was the phenomenon of contractors feeding workers in our U.S. war plants: the Crotty Brothers from Boston, the Slater System of Philadelphia (now known as ARA), Fred Profit from Detroit, and many regional operators.

Once the war was over, these same companies continued to not only function, but to expand as the country returned to normalcy. In addition to industrial clients, the impact of the GI Bill of Rights on educational communities, such as colleges, trade schools, and universities, enhanced the account books of the foodservice contractors.

One of the attractions of working for these companies (especially for managers and chefs at that time) was the five-day schedule with weekends off—a rare happening in the public sector.

One of the more creative companies of that time (and still operating today under the capable leadership of Nick Valenti) was Restaurant Associates Corp.

In 1964 their list of operations read as follows: Charley Brown’s, Tavern on the Green, the John Peel Room, and Douglaston Steak House (both located on Long Island), the Tower Suite, The Forum of the Twelve Caesars, Mama Leone’s, and La Fonda del Sol.

They also popularized the Italian word for casual café, with The Trattoria, the Zum Zum (a quick-service concept), The Brasserie, and the Newark Airport.

The crown jewel of the company was the Four Seasons. In this writer’s mind, this was the greatest collection of individual restaurants in New York’s restaurant history.

The two men responsible for this restaurant development were Joe Baum and Jerry Brody. Joe was a marketing genius and innovator, and Jerry was a great manager and deal maker.

This was also the beginning of the phasing out of landmark “smart set” operations such as the Stork Club, the El Morocco, the Colony, and the Copacabana, to name a few. The famous “Breakfast at Longchamps” chain would soon join them.

The interstate highway system was about 60 percent completed by the latter part of the decade, and the old motor courts and ageing motels were being replaced by Quality Inns, Best Westerns, and Howard Johnson Motor Lodges.

One of the more interesting stories deals with the founding and growth of the Holiday Inns of Memphis, Tennessee. It seems a young man by the name of Kemmons Wilson took his family for a three-week trip to parts of the country and was appalled by the lack of family accommodations.

When he returned home, he put together a group of investors and, as a result, gave birth to the Holiday Inn chain of hotels. Need I say more?

The growth of the new type of highway accommodations also meant new restaurants competing with longtime established operators, and travelers now had a choice of various types of cuisine.

Most of the new housing had swimming pools, catering capabilities, and conference centers. The hospitality landscape was changing and interstate interchanges were now becoming sought after by an army of multi-unit foodservice companies as well as lodging groups.

One of these lodging groups slowly but surely moving ahead was Marriott, a company that started out as operators of drive-in restaurants, to motor lodges and fine hotels—in only two generations. First, J. Willard Marriott Sr., now deceased, and then his son Bill led it to become the largest hotel chain in the world.

The early 1970s witnessed the first sign of casual foodservice. TGI Fridays, Houlihan’s, Ground Round, and later, Ruby Tuesday and Applebee’s sprang up all around the country. Bob Evans, Waffle House, and Huddle House joined those who were surrounding the interstate interchanges, to create what was to become known as “the strip.”

One of the most industry-wide developments to take place in the latter part of the ’70s was the expansion—one might even call it an explosion—in foodservice education for all disciplines.

The CIA moved to New York State and started to expand its facilities and curriculum. Johnson & Wales University duplicated that growth, and today most state universities have courses in foodservice management and culinary arts.

The ProStart program developed by the National Restaurant Association Educational Foundation (NRAEF) has helped high school students to hone their desire to create and perform in the foodservice industry. There is no question that the industry’s tremendous growth could not have taken place or continued without the contributions of the educational community.

While the more responsible operators were exercising good judgment when it came to monitoring guests’ consumption, they too were feeling the effects of the insurance crisis and its skyrocketing costs. In response to the seriousness of the problem, industry associations launched a series of server training programs, which are still available today.

These programs have been effective and many insurance companies now require them, some even offering a discount to those operators who require servers to attend them.

Next came the no-smoking issue. I will not spend time discussing what then was a very controversial issue.

Today we are in the “menu management” era. Not only do the “food police” want trans fats wiped from the face of the earth but they will soon launch a “sack the salt” offensive. This will urge chefs to reduce the salt content by 50% in their recipes. The would-be menu managers will not rest until every ingredient of every menu item is printed on every menu.

During the last half of the ’70s and most of the ’80s, the “eating out” public was being dazzled by nouvelle cuisine. At first it was more prominent in urban areas, but by the end of the ’80s and into the early ’90s it was being served everywhere.

One of the most dramatic changes occurred in the public’s attitude toward and interest in the culinary arts and its players. In 1986, Julia Child suggested that a not-for-profit foundation be formed to keep alive the philosophy, ideals, and practices that earned the late James Beard his reputation as the father of American gastronomy.

As a result, the James Beard Foundation became a reality. Each year at its annual awards event, the best and brightest of the industry are recognized for their achievements.

Between the Beard event and the popularity engendered by the Food Network, American culinary arts and its craftsmen and craftswomen had truly arrived. One of the most visible aspects was the food presentation itself: side dishes slowly disappeared and the main plate resembled a portrait.

If I may say so, one of the great artisans of that era was a gentleman by the name of André Soltner, who for more than 25 years was the chef-owner of New York City’s legendary French restaurant, Lutèce.

Over that same 25-year spread, four separate food critics for the New York Times rated Lutèce four stars—a feat yet to be matched. Soltner is now associated with The French Culinary Institute in New York City.

A by-product of this fascination with food and those who prepare it is the increase in media attention. Almost every newspaper, major magazine, and TV station started devoting more space, time, and ink to restaurants, wine, and ingredients.

Chefs were becoming media stars. Bobby Flay, Emeril Lagasse, Wolfgang Puck, Mario Batali, Rachael Ray, and Lidia Bastianich all became household names. Not only were they media stars but most have become best-selling authors. In fact, it is almost mandatory that in order to arrive as a culinary star, you must be published at least once.

The growth of chain restaurants, in both diversity and numbers, was changing the competitive landscape throughout the United States. This change also included a new type of competition, the local mini-chain. I call them signature chains.

Examples are Bobby Flay, Wolfgang Puck, Steve Hanson, the Brennan Family, David Boulud, Danny Meyer, Jean-Georges Vongerichten, Drew Nieporent, and the list goes on.

In many instances their operations are in the same marketing area. This does not diminish their impact. As I have said many times, their reputations have become a great asset. This asset makes them attractive to property owners as well as their investors when they are selecting new locations.

As the saying goes in Hollywood: “They are bankable.”

Our next era includes a new century, catering to an educated and sophisticated consumer, and the question of how casual we will get.

I would be remiss, when discussing the progress and growth of our industry these last 78 years, if I didn’t acknowledge the tremendous contributions made by our purveyor partners.

From the development of laborsaving equipment to eye-popping interior design, to providing exciting new food products, to technological support systems—they have served and continue to serve the industry well. They have been of great assistance in bringing the industry to a level of sophistication that has not only grown in size but in management skills as well.

What does the future hold? … We will see more mergers, particularly in the QSR sector.

Why? Many small companies presently with 5, 10, 15, or 20 units are hoping to become another Five Guys or Shake Shack and they can’t all make it. In addition, more capital venture groups will fight for control of the larger chains.

Labor costs will continue to increase as long as government entities continue to raise the floor (also known as the minimum wage), as will food costs. More supermarkets and convenience stores will go on expanding their takeaway food offerings and in some instances add dining areas in their stores.

I do believe the Service Employees International Union will become more active in attempting to represent the QSR sector employees, as per their participation in the $15 per hour wage issue.

Management must give improved service a high priority. Most think they do; however, that’s not what consumers are saying.

Today’s consumer is the smartest, best informed, and social media educated that the business community has ever had to deal with. Many of them don’t take the time to complain on the spot; they simply announce their dissatisfaction to the world via Yelp or other similar venues.

Here are some of their complaints: “Lack of friendly disposition,” 56%, and “Not stopping by regularly to see and check if I need anything else,” 50%.

Another survey: “A bad attitude really turns me off,” and “If they’re not happy with the job, then find something else to do.” These next two are on all the lists: “When picking up the check, asking ‘Do you need any change?’ and ‘Is everything all right?’ every five minutes, as opposed to ‘I’ll be right back with your change’ and ‘Can I get you anything else?’ ” If something is wrong, the guest will let you know—if you remain aware of them.

To sum up the service issue, may I be so bold as to suggest that you remember, when interviewing for servers, that “Attitude Defines Service.” Using this as a measurement of the applicant, what was your impression?

I leave you with this basic premise that my dad uttered to me so very long ago: “The best-prepared meal in the world cannot survive poor service; however, good service can enhance an average meal.”

When I started this abbreviated memoir, I realized that I couldn’t possibly cover almost 80 years in 3,000 words and there would be many areas left untouched. In some future column(s), I will discuss particular individuals I have known who have had a positive influence on this rewarding industry we call foodservice.

I hope you’ve enjoyed sharing “Looking Over My Shoulder at 90” with me. Thanks for taking the time.

This is the second of a four part series that is an overview of the 78 years I have been associated with the foodservice industry. Part 1 described the three or four years before World War II, the postwar growth of the industry, and how the GI Bill of Rights and the National Interstate Act were catalysts for that growth.

This installment covers the diversification that the 1960s and ’70s introduced to the industry.

The ’60s could be called the transitional decade for both the hospitality industries of foodservice and lodging. While there were many regional foodservice companies, there were few, if any, national multi-unit operators.

Two men were about to change that: Ray Kroc of McDonald’s fame and James McLamore of Burger King.

Another popular operation—though not as large as the home of the Big Mac or the Whopper—was Burger Chef, which was sold to General Foods Corporation and eventually went out of business.

Its demise was due to General Foods’s decision not to retain any of Burger Chef’s management. This decision proved to be a costly $30 million mistake, and in the ’60s that was a lot of money! As a by-product of this new type of operation, the term “fast food” became a part of our lexicon.

Today we describe them as quick-service restaurants.

Another aspect of foodservice growing at a prodigious rate was the phenomenon of contractors feeding workers in our U.S. war plants: the Crotty Brothers from Boston, the Slater System of Philadelphia (now known as ARA), Fred Profit from Detroit, and many regional operators.

Once the war was over, these same companies continued to not only function, but to expand as the country returned to normalcy. In addition to industrial clients, the impact of the GI Bill of Rights on educational communities, such as colleges, trade schools, and universities, enhanced the account books of the foodservice contractors.

One of the attractions of working for these companies (especially for managers and chefs at that time) was the five-day schedule with weekends off—a rare happening in the public sector.

One of the more creative companies of that time (and still operating today under the capable leadership of Nick Valenti) was Restaurant Associates Corp.

In 1964 their list of operations read as follows: Charley Brown’s, Tavern on the Green, the John Peel Room, and Douglaston Steak House (both located on Long Island), the Tower Suite, The Forum of the Twelve Caesars, Mama Leone’s, and La Fonda del Sol.

They also popularized the Italian word for casual café, with The Trattoria, the Zum Zum (a quick-service concept), The Brasserie, and the Newark Airport.

The crown jewel of the company was the Four Seasons. In this writer’s mind, this was the greatest collection of individual restaurants in New York’s restaurant history.

The two men responsible for this restaurant development were Joe Baum and Jerry Brody. Joe was a marketing genius and innovator, and Jerry was a great manager and deal maker.

This was also the beginning of the phasing out of landmark “smart set” operations such as the Stork Club, the El Morocco, the Colony, and the Copacabana, to name a few. The famous “Breakfast at Longchamps” chain would soon join them.

The interstate highway system was about 60 percent completed by the latter part of the decade, and the old motor courts and ageing motels were being replaced by Quality Inns, Best Westerns, and Howard Johnson Motor Lodges.

One of the more interesting stories deals with the founding and growth of the Holiday Inns of Memphis, Tennessee. It seems a young man by the name of Kemmons Wilson took his family for a three-week trip to parts of the country and was appalled by the lack of family accommodations. When he returned home, he put together a group of investors and, as a result, gave birth to the Holiday Inn chain of hotels. Need I say more?

The growth of the new type of highway accommodations also meant new restaurants competing with longtime established operators, and travelers now had a choice of various types of cuisine. Most of the new housing had swimming pools, catering capabilities, and conference centers.

The hospitality landscape was changing and interstate interchanges were now becoming sought after by an army of multi-unit foodservice companies as well as lodging groups.

One of these lodging groups slowly but surely moving ahead was Marriott, a company that started out as operators of drive-in restaurants, to motor lodges and fine hotels—in only two generations. First, J. Willard Marriott Sr., now deceased, and then his son Bill led it to become the largest hotel chain in the world.

The early 1970s witnessed the first sign of casual foodservice. TGI Fridays, Houlihan’s, Ground Round, and later, Ruby Tuesday and Applebee’s sprang up all around the country. Bob Evans, Waffle House, and Huddle House joined those who were surrounding the interstate interchanges, to create what was to become known as “the strip.”

One of the most industry-wide developments to take place in the latter part of the ’70s was the expansion—one might even call it an explosion—in foodservice education for all disciplines. The CIA moved to New York State and started to expand its facilities and curriculum.

Johnson & Wales University duplicated that growth, and today most state universities have courses in foodservice management and culinary arts. The ProStart program developed by the National Restaurant Association Educational Foundation (NRAEF) has helped high school students to hone their desire to create and perform in the foodservice industry.

There is no question that the industry’s tremendous growth could not have taken place or continued without the contributions of the educational community.

Next, part 3: The industry’s continued growth, government’s expanding role in the industry, and America’s ascension to culinary heights.

This is the third in a series of articles dealing with my observations during the 78 years that I have been involved with the foodservice industry.

It began in my family’s restaurant in Philadelphia when I was 12 years of age, after school and weekends.

While my participation has not yet concluded, my last full-time employment was with the New York State Restaurant Association from 1961 to 2000, as president and CEO. I now am able to share my views on those issues that I feel are pertinent to the industry.

The ’70s marked the beginning of the social issues, which would affect the industry then and continue to do so today. First, there was the issue of driving while intoxicated (DWI).

The issue itself was not new. However, the increased number of auto accidents and fatalities resulting from this condition aroused the general public and gave birth to Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD).

This organization spearheaded an effort to get drunk drivers off the roads. During this process, a greater number of victims and survivors sought damages in the courts from the drunk drivers and from the on-premises licensees as well. This sent liquor liability insurance rates through the roof, and in many cases insurance companies stopped writing the coverage.

The result? Many licensees took a great risk and ran “naked”—in other words, without it.

While the more responsible operators were exercising good judgment when it came to monitoring guests’ consumption, they too were feeling the effects of the insurance crisis and its skyrocketing costs. In response to the seriousness of the problem, industry associations launched a series of server training programs, which are still available today.

These programs have been effective and many insurance companies now require them, some even offering a discount to those operators who require servers to attend them.

Next came the no-smoking issue. I will not spend time discussing what then was a very controversial issue.

Today we are in the “menu management” era. Not only do the “food police” want trans fats wiped from the face of the earth but they will soon launch a “sack the salt” offensive. This will urge chefs to reduce the salt content by 50% in their recipes.

The would-be menu managers will not rest until every ingredient of every menu item is printed on every menu. I will have more to say about the regulatory climate in Part 4 of this series.

During the last half of the ’70s and most of the ’80s, the “eating out” public was being dazzled by nouvelle cuisine. At first it was more prominent in urban areas, but by the end of the ’80s and into the early ’90s it was being served everywhere. One of the most dramatic changes occurred in the public’s attitude toward and interest in the culinary arts and its players.

In 1986, Julia Child suggested that a not-for-profit foundation be formed to keep alive the philosophy, ideals, and practices that earned the late James Beard his reputation as the father of American gastronomy.

As a result, the James Beard Foundation became a reality. Each year at its annual awards event, the best and brightest of the industry are recognized for their achievements. Between the Beard event and the popularity engendered by the Food Network, American culinary arts and its craftsmen and craftswomen had truly arrived. One of the most visible aspects was the food presentation itself: side dishes slowly disappeared and the main plate resembled a portrait.

If I may say so, one of the great artisans of that era was a gentleman by the name of André Soltner, who for more than 25 years was the chef-owner of New York City’s legendary French restaurant, Lutèce. Over that same 25-year spread, four separate food critics for the New York Times rated Lutèce four stars—a feat yet to be matched. Soltner is now associated with The French Culinary Institute in New York City.

A by-product of this fascination with food and those who prepare it is the increase in media attention. Almost every newspaper, major magazine, and TV station started devoting more space, time, and ink to restaurants, wine, and ingredients. Chefs were becoming media stars.

Bobby Flay, Emeril Lagasse, Wolfgang Puck, Mario Batali, Rachael Ray, and Lidia Bastianich all became household names. Not only were they media stars but most have become best-selling authors. In fact, it is almost mandatory that in order to arrive as a culinary star, you must be published at least once.

The growth of chain restaurants, in both diversity and numbers, was changing the competitive landscape throughout the United States. This change also included a new type of competition, the local mini-chain.

I call them signature chains. Examples are Bobby Flay, Wolfgang Puck, Steve Hanson, the Brennan Family, David Boulud, Danny Meyer, Jean-Georges Vongerichten, Drew Nieporent, and the list goes on.

In many instances their operations are in the same marketing area. This does not diminish their impact.

As I have said many times, their reputations have become a great asset. This asset makes them attractive to property owners as well as their investors when they are selecting new locations. As the saying goes in Hollywood: “They are bankable.”

Our next era includes a new century, catering to an educated and sophisticated consumer, and the question of how casual we will get.

This is the final installment of this series, which I have titled “Looking Over My Shoulder at 90.” It summarizes some of the events that have taken place within the foodservice industry from 1939, when I first started to help out in my family’s restaurant in Philadelphia, to the present.

You may not agree with my selection of events, but they did happen.

The last half of the 1980s and most of the ’90s witnessed not only great overall growth, but the full impact of the interstate highway system that Congress created back in the ’50s and which has come full circle. Because of it, downtown commercial centers became deserted and, thus, restaurant growth moved to the suburbs.

That also was where the megamalls were being built and a new marketing concept called “food courts” was changing the competitive climate. Instead of avoiding the competition, it was next door.

Another trademark of suburban life was the growth of “strip malls.” These groups of small shops with ample parking spaces were popping up all over the place. That’s where you found pizza and sandwich shops.

You would also find boutique restaurants serving delicious food and being rewarded with great business. As I said in a previous column, the ability to purchase a professionally prepared meal is no longer limited to major metropolitan areas; it now can be found anywhere.

I would be remiss, when discussing the progress and growth of our industry these last 78 years, if I didn’t acknowledge the tremendous contributions made by our purveyor partners. From the development of laborsaving equipment to eye-popping interior design, to providing exciting new food products, to technological support systems—they have served and continue to serve the industry well.

They have been of great assistance in bringing the industry to a level of sophistication that has not only grown in size but in management skills as well.

What does the future hold? … We will see more mergers, particularly in the QSR sector. Why? Many small companies presently with 5, 10, 15, or 20 units are hoping to become another Five Guys or Shake Shack and they can’t all make it.

In addition, more capital venture groups will fight for control of the larger chains.

Labor costs will continue to increase as long as government entities continue to raise the floor (also known as the minimum wage), as will food costs. More supermarkets and convenience stores will go on expanding their takeaway food offerings and in some instances add dining areas in their stores.

I do believe the Service Employees International Union will become more active in attempting to represent the QSR sector employees, as per their participation in the $15 per hour wage issue.

Management must give improved service a high priority. Most think they do; however, that’s not what consumers are saying.

Today’s consumer is the smartest, best informed, and social media educated that the business community has ever had to deal with. Many of them don’t take the time to complain on the spot; they simply announce their dissatisfaction to the world via Yelp or other similar venues.

Here are some of their complaints: “Lack of friendly disposition,” 56%, and “Not stopping by regularly to see and check if I need anything else,” 50%.

Another survey: “A bad attitude really turns me off,” and “If they’re not happy with the job, then find something else to do.”

These next two are on all the lists: “When picking up the check, asking ‘Do you need any change?’ and ‘Is everything all right?’ every five minutes, as opposed to ‘I’ll be right back with your change’ and ‘Can I get you anything else?’ ” If something is wrong, the guest will let you know—if you remain aware of them.

To sum up the service issue, may I be so bold as to suggest that you remember, when interviewing for servers, that “Attitude Defines Service.” Using this as a measurement of the applicant, what was your impression?

I leave you with this basic premise that my dad uttered to me so very long ago: “The best-prepared meal in the world cannot survive poor service; however, good service can enhance an average meal.”

When I started this abbreviated memoir, I realized that I couldn’t possibly cover almost 80 years in 3,000 words and there would be many areas left untouched. In some future column(s), I will discuss particular individuals I have known who have had a positive influence on this rewarding industry we call foodservice.

I hope you’ve enjoyed sharing “Looking Over My Shoulder at 90” with me. Thanks for taking the time.